Panda OS

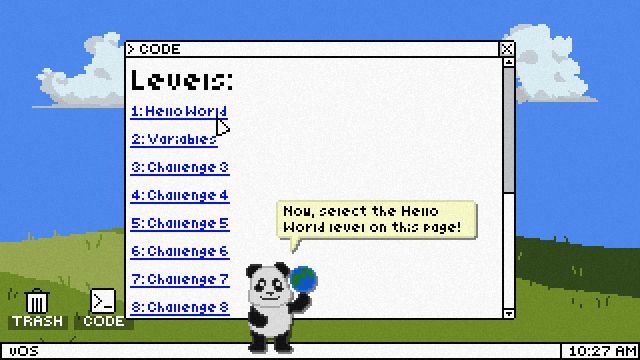

PandaOS is a game that teaches people how to program in C#. The game is able to run user-entered code and evaluate their performance in various puzzles and give them hints or feedback to guide them toward the right solution. This project started as my senior thesis project in high school, but I am still actively working on it as a passion project.

Target Audience

The video game industry is huge, nearly $180 billion a year huge, even dwarfing the movie and music industry. It's no surprise to hear that the biggest demographic for video games are teenage boys. What you might not know is the largest demographic by race is black teenagers. 83% of non-hispanic black teens play video games[1]. To put this number into perspective, the number of white teens that play games is “only” 71%, with Hispanic teens being close behind at 69%.

Even with great diversity among gamers, the amount of diversity in game development is severely lacking. Only 4% of game developers identify as “Black, African American, African or Afro-Caribbean”, and 10% identify as “Hispanic or Latino/Latina/Latinx”[2]. The majority of course is white, at 67% of people surveyed.

These statistics are reflected in the diversity of characters in gaming and their depictions. Characters of color in games are few and far between, especially when it comes to original characters and not depictions of real people (eg. sports games).

Because of the disparity in diversity between gamers and game developers, I wanted to use this project as a way to introduce teens of color to game development. There are already a few games that teach coding, so my goal for this project is to both provide a learning tool and a sandbox that experienced coders can also use.

Technical Challenges

I was adamant the game should teach a real language like C# while still being accessible to people who have never written a line of code. If you listen closely you'll hear the sounds of security analysts losing their minds in the distance. Giving users the ability to run whatever code they want also gives them the ability to break the game in infinitely many ways. One security analyst on Reddit told me about my idea: “Just don't. No game concept is worth that trouble". As Exodrifter put it in her article about compiling C# at runtime in Unity, this idea seems “like the equivalent of equipping bears with flaming chainsaws”, though she goes on: “...it has several practical advantages”.

Ignoring the words of caution, I trekked on. The first challenge was to take user input and convert that to code we can run. There are a few great resources about accomplishing this in Unity and I got it working after a few weeks of trial and error. There are a few caveats, however.

Normally, anyone who wanted to install the game would also have to separately install the Mono SDK in order to run code. This makes the installation process annoying and time-consuming. To circumvent this issue, the Mono.CSharp package is included inside of the game. This is possible through some sort of dark techno-wizardry. Luckily, there were people who had attempted this before me and shared their journey so I didn't have to go in blind.

Great, so now you can run code and compile it inside the game. This is what I want, of course, but it's a problem if you can run any code. The code the user runs should be “sandboxed” so that none of their code will affect the base game.

What I did was split the code in two: the code that runs the base game and the code that the player was allowed to access. The player is only given access to what they need, so no outside code was relied upon that could let the user break stuff. The downside to this approach is that if I can't use outside code, I have to create my own implementation from scratch. Basically, I reinvented the wheel.

While it took a significant amount of time, the final solution ended up being rather elegant I have complete control over the very specific under-workings of what the player can do it's much easier to know what code the player is actually running, which is useful for building the puzzles and tutorials.

Sources

1. "Chapter 3: Video Games Are Key Elements in Friendships for Many Boys". Lenhart, Amanda.

2. "Developer Satisfaction Survey (DSS) 2021". Weststar, Johanna, et al.